- Home

- Stanley Middleton

Valley of Decision Page 2

Valley of Decision Read online

Page 2

‘I suppose it’s not well paid,’ David had said, feeling it his duty to ensure his family understood implications.

‘What’s the salary?’

David told him. His father touched his bristling moustache as if doing arithmetic.

‘That’s more than you’d get if you started with me,’ he said.

‘The big differences will come at the other end,’ the son argued.

‘Do they, then? Do they?’ Glazing of eyes. ‘Yes. Yes. If you get there.’

Horace had no ideas of founding a business dynasty. If David wished to become a schoolmaster, that would do; in time he would be rich compared with his colleagues, but that was no reason for largesse now.

Here the mother had intervened.

‘All they’ll be able to afford on David’s salary,’ she said, ‘is a semi-detached.’

‘What’s wrong with that?’ Horace went through the motions of opposition.

‘I don’t want my son in some poky little place when there’s no need.’

‘But if that’s all they can afford?’

‘What will people say?’

‘That I’m mean,’ Horace said. ‘But I don’t mind that. On the other hand, they may think the boy’s too independent to accept my charity, and that will be much in his favour.’

‘You talk to him,’ she commanded, beautiful still at fifty, proud of her husband, quick to defend his dryness, adored in return.

When Mary’s opera company finally found itself in financial trouble and disbanded, thus making up her mind for her, father Blackwall had offered them money for a house. Neither of the young people had made much fuss about acceptance, disappointing him, but had not chosen a house very much grander than they could afford on their joint salaries.

‘It’s quite pleasant,’ Joan Blackwall had said to her husband.

‘You mean it’s not what you would have picked for them.’

‘No. But it means we can buy Mary a grand piano.’

‘You should have bought that first,’ Horace, indulgently expansive, ‘and built the house round it.’

‘They could have ours for all the playing it gets.’

‘Ah.’ Horace lay back and invited his wife to perform. They moved upstairs, almost formally, as if observing some protocol.

‘Let’s have some favourites.’ He loved patronage of this sort, knowing how assiduously his wife kept up her practice. The opening of Mozart’s Sonate Facile, Chopin’s E flat Nocturne, the three Brahms Intermezzi, op. 117, and finally, brilliantly, the last movement of Bach’s ‘Italian’ Concerto. As she played he sat quite still, neither kicking nor shifting on his hams. She closed the lid with her usual comment: ‘Too many wrong notes.’

He nodded, then shook his head, making no great play with denial. They put out the lights in the drawing room and went downstairs again, both satisfied by the recital. On such nights the television was left untouched.

As a boy David had sometimes listened to these performances from his room but had never sat in, though he knew he would be welcome, that his presence would have pleased his parents. Horace Blackwall loved his wife always, but when she played the Bechstein he seemed lifted out of himself. His son never grasped how this happened; his father was no musician, had to be bullied to attend a concert or opera, but regarded these perhaps once-weekly performances as not unlike the twice-yearly Eucharist he attended at St Jude’s; these were numinous. They did not make him wish his life otherwise, but were of a different order from a glass of fine claret or even, rare-favoured delicacy, his wife’s lardy cake.

The bedroom light was still on, but Mary lay fast asleep, face perfectly in repose. He drew the sheets up to her chin, but she did not stir. The dark hair, blue-back, seemed hardly disarranged by the pillow, and the shape of cheekbones, nose, mouth was utterly satisfying. Tired as he was, he wished she would open her light blue eyes, lifting the long lashes, but he knew that unlikely. He undressed at speed, wound the alarm, set the radio and slipped in beside her. She stirred, and immediately settled back.

The Blackwall men loved their wives.

2

AT A QUARTER to eight the next evening the four Blackwalls occupied the table at the end of dinner. Horace issued his orders.

‘David can help his mother carry the dishes out to the machine.’

‘I’ll do it,’ Mary said.

‘You’ll stay with me. Perhaps later you can sing. Your mother thinks you should both be in bed early tonight, so we shall be sending you off at nine thirty.’ He consulted his watch and the grandfather clock behind him, then blew out the candles. ‘Don’t like these things. Dangerous, and they stink.’

He led Mary to the drawing room where they sat side by side on the second settee.

‘Must have you in good form for tomorrow and Saturday.’ He continued in the grum-and-gruff vein he sometimes adopted with his daughter-in-law, telling her how his wife had inveigled him into parting with an immense cheque to pay for tickets for dinner and the Saturday performance at Rathe Hall.

‘Even David said the Purcell was good.’

‘But the food. The grub.’ The word was plucked from some earlier vocabulary, perhaps that of the comics or library books he had read in his boyhood. ‘Holkham Tait’s no idea.’

‘They’re using an outside caterer.’

‘Is that likely to be better? He’ll just spread mushrooms in sauce over everything.’

Blackwall senior had little interest in haute cuisine; he had a healthy appetite which needed no cosseting, and preferred, as he said often, plain fare, but on these social occasions he enjoyed parading himself to his daughter-in-law as a man of the world.

‘Colonel Tait’s a bit of a recluse, isn’t he?’

‘Did he show up, then?’

‘We were backstage. I didn’t see him. Perhaps he did.’

‘He’s old now. Older than me, anyhow. Seventy. And spends a good part of the year abroad. Not that he’s poverty-stricken. He farms in a big way. But he’s not at everybody’s beck and call, I’ll give you that. I’m surprised he gave permission for this week’s disruption.’

‘Elizabeth Falconer’s a persuasive woman.’

Horace Blackwall coughed, checking conversation, saying no more himself as if Mary had broken a taboo. David returned with his mother.

‘Are you two tittle-tattling?’ Joan asked.

‘Of course.’ Her husband.

‘Colonel Tait’s love for Lizzie Falconer,’ Mary added, mischievously, not certain that her father-in-law would approve.

‘It’s over,’ Joan Blackwall said, finding herself a brocaded chair to face her husband.

‘How do you know that?’ Horace.

‘He told me so, himself.’

They all laughed, but nervously, as if not disputing the claim.

‘How’s she singing?’ Horace asked. ‘That’s what I want to know about. I’ve paid good money.’

‘Marvellously.’

‘She’s keeping her practice up?’

‘Must be. She’s due to go back to it. She’ll have to lose a stone or two.’

‘Can’t have too much of a good thing.’ Horace was pleased to be sitting with his daughter-in-law, pleased with himself, his wife, her cooking, the time of night.

‘Was she a good teacher?’ Joan Blackwall asked Mary.

‘I hardly saw her at the RCM. The odd consultation lesson. She was in Bayreuth, or New York, or Sydney. But she was good. She bothered to listen.’

‘She thought you would make it,’ David said.

‘She was kind to me. It was her recommendation to Will Broderick that got me into Omnium.’

‘And now you’re both retired up here?’ Mrs Blackwall said.

‘She won’t stay long,’ David prophesied. ‘She’s not sung out her old engagements, and she’s been here three years. She’ll be signing up again. Won’t leave it there.’

‘How old is she?’

‘Thirty-eight, would you say, Mary? Thereabo

uts.’

‘And what will her husband do about her setting off again?’ Horace.

‘There’s a very great deal of money in it,’ David said. ‘Cash talks.’

‘He’s not short.’ Mary.

‘No. But she’s had enough as the squire’s wife.’

‘Has she told you?’ Mary, mocking.

‘You know her better than I do,’ he said sombrely. ‘She’s ambitious, a singer. She thinks of herself. Can hardly do otherwise in her position. Sir Edward has had her home now for some months each year. People did say she was just a bit frightened of singing herself out.’

‘No sign of it,’ Mary said.

‘There must be,’ Horace Blackwall sounded interested, ‘quite a difference between Rathe Hall and Purcell and howling Wagner over immense distances and a full orchestra. It’s nothing to do with music really.’

Nobody took him up. David had his eyes shut as if he were dropping asleep. When they had all refused alcohol Horace invited Mary to sing. She stood up.

‘I know what I like,’ he said, guying himself.

‘Not more than two,’ his wife warned, moving towards the piano. ‘Mary’s tired.’

He chose, immediately, without hesitation. ‘Have you seen but a bright lily grow?’

‘And?’ Joan looking for music.

‘“The Lass with the Delicate Air”.’ He smiled in anticipation, pleased that he could make such a demand. He conducted to himself, though one could not tell which song.

Mary sang, standing by the piano, one hand splayed on the lid. Her voice rang with no strain, no fatigue, soared about the big room, clipping the notes in the centre, taking the upward rising scale of the first song like a jewelled stairway. She smiled vaguely, impersonally in the direction of her father-in-law. ‘Oh, so white’, the tone exactly reflected the purity, the strength of her musicality and the transient, elusive beauty of whiteness in nature that resided permanently, ‘oh, so white, oh so soft’, in the lady, in Mary. Small lines furrowed at the corners of her eyes, her mouth; her skin seemed, trick of the light, to have lost something of its bloom. She was tired, David decided, but it did not show in the voice. That sprang, leaped, couched, settled with creamy power.

Horace, David knew, was particularly fond of the high notes at the end of ‘The Lass’. Under Mary’s skill the simple device, the soaring and dropping, had about it an innocence, a freedom from the sensual yet based distantly, obliquely in sexuality, a richness of some golden, naked age that existed only out of the corner of the eye. David himself stretching, knowing exactly how his wife would perform, would bring the effect off, was yet moved by it. It was distilled, freed from impurity, but caught the light artlessly like burn water. His father’s eyes brightened with tears; the old man did not mind who saw him draw out, shake loose his handkerchief to wipe them off, but the voice with which he thanked her was steady enough.

‘One more,’ almost peremptorily from Joan Blackwall. She had noticed her husband’s joy, and would cover it with a different, livelier pleasure. She sorted through a small pile of music, held up a piece briefly, open, to Mary and then straightened it on her stand. David, staring, had no time to make out the title, but the first sharp chord, the pace now furious but steady, made him aware, and his father, of what happened. Purcell’s ‘Hark the Echoing Air’, lively, brisk, trumpet-bright, echoed from the panels of the room, bounced, ran headlong into the ears, gold, speedy, a marvel. Each semiquaver she touched burst with the flash of a grenade, small, lilting, lifting, a-dance, sparking with young life’s exuberance. ‘And all around pleased Cupids clap their wings’, and the accompaniment, needle-sharp, applauded the voice, little handclaps of musical appreciation, tripping, shifting perfumed air, clap, clap, clap, delicate in confidence, chasing, matching the racing voice so that when the second brilliance of the repeat ended with a touch, an off-handedness of allargando, the two men both sat upright, wanting the light, the run of tiny, life-giving explosions, again, again, again.

Mary smiled broadly. Her mother-in-law wiped nonexistent sweat from her brow. The men were smiling, sitting alert and radiant, wide awake, angels in bright daytime.

‘Marvellous,’ Horace said.

‘Well done, both.’ David.

‘We married a couple of winners,’ the father said. ‘Don’t let anyone tell you otherwise.’

The four sat for perhaps another ten minutes, completely content with the others, but immersed still in the music. They spoke, now and again, as if to disperse the solipsism of their pleasure; the longest passage between Joan and Mary concerned the breakdown of a washing machine, but that itself took the form of a text to be set by Purcell, a few incomplete statements needing music to match them to the hour.

‘Come on,’ David said, yawning again. ‘It’s time.’ The others rose; he kissed his mother here, though he would kiss again by the door.

‘That was a treat,’ Horace touched his daughter-in-law on the arm, ‘and a half.’ He was fond of his childhood’s phrases.

Mary seemed to expand as she put on her outdoor clothes. Now, hatted, she stood larger than life, a Valkyrie, formidably tall, not the slim girl who’d dazzled them with brightness of voice.

‘Ready, my lord,’ she informed her husband. She kissed the parents.

‘Save something for Saturday,’ Horace said.

‘You’ll get your money’s worth.’

‘In mushroom sauce.’

They laughed hoarsely in the hall and the heavy door clanged, dividing their harmony. Horace switched on the television with lacklustre eye, knowing he had to pass time until he went upstairs to bed. His wife pottered round in the kitchen; she could always find a chore to combat the bathetic, but he had no such art. David drove home quietly and saw Mary’s eyes closed against undipped headlights. The road shone greasily; their house was cold and the electric blankets unwarming. On the wall the quartz clock ticked synthetically and louder than usual.

‘Another day gone,’ she said, plugging in the kettle.

‘You’re not making another drink?’ he complained.

‘We’ve got to give the blankets half a chance.’ She seemed livelier. ‘Enjoy it?’

‘I’m always too tired, but, yes. You transform the old man. I wouldn’t have said he was all that keen on music, but look at him tonight.’

‘He was crying, David.’

‘Yes.’

‘Why was that?’

‘Who am I to say?’ He spoke sharply, as if annoyance had woken him from lethargy. ‘He feels strongly, and that’s how it shows itself. He’s getting old.’

‘He’s fifty-eight, and young at that.’

David did not answer, but banged about the house closing up. Perhaps he felt betrayed by his father’s overt emotionalism, she did not know, or perhaps he’d had an unsatisfactory day at school. She sipped her weak instant coffee, wishing him quiet and sitting by her.

‘Liz Falconer rang me up at work,’ she told him. He did not answer, waited for further information. Mary seemed unwilling to continue without his questions.

‘Um?’ he compromised, then capitulated. ‘About tomorrow?’

‘No. She was sounding me out about a singing job.’ She used the flat words to pacify him. ‘In America. She’s singing for two seasons there, she says. In a year’s time.’

‘Wagner?’

‘No, she’s already committed to that in Bayreuth and Paris. This is Mozart, Meyerbeer and perhaps Dido, she hopes. And she says she can get me into the act.’

The steadiness of the tone belied the lightness of the words.

‘Is she sure?’ he asked.

‘No. Not really. It depends if I want it, but then she’ll use her influence. She couldn’t promise anything. She made that clear.’

‘And you said?’

‘That I’d have to think about it, and consult you.’

They both sat at either end of a table laid for breakfast, awake, troubled for the other. Ten o’clock struck.

‘Do

you want to hear the news?’ she asked.

‘No.’ He shook his head, sighing, like a dazed boxer. ‘Well, what do you think then?’

‘I don’t know.’

A spurt of anger jangled in him.

‘That means you’d like to go,’ he said.

They did not stir, but she watched him as he idly but methodically moved spoons and plates about the tablecloth.

‘I don’t blame you,’ he continued, but dully, as if he were hampered by a cold in the head. ‘It’s a great opportunity.’

‘I’m not sure.’ Mary spoke firmly now, as his father spoke about imports of Swedish furniture or the buying of shares in office blocks. ‘There’ll be some travelling because there’ll be at least two companies, and I shall almost certainly be in the “B” if not lower. And that’s not altogether comfortable. Digs,’ she said laughing, ‘and men. And women.’

‘But you’ll see the world.’ It sounded feeble.

‘It will only be worthwhile if I do well enough to go on. And you know what that means.’

‘If you don’t do it, you’ll blame yourself for the rest of your life.’

‘I wonder,’ she said.

At the words love gushed in him, like the bursting of an artery, a warm, a killing comfort. It meant nothing; she would modify the meaning in the next sentence in all probability, but the three syllables spoke with a reasonableness that masked love, a mathematical equation, a quantifying of her affection for him.

‘Are you bored with your work here?’ he asked.

‘No, I’m not. There’s plenty to do, and I’ve got the hang of it. I like the people, and this house.’ The blue eyes widened. ‘Then there’s you.’

‘Yes,’ he said.

‘What do you think?’

‘If you want to go, you grab the chance. “There is a tide in the affairs of men . . .”’

Valley of Decision

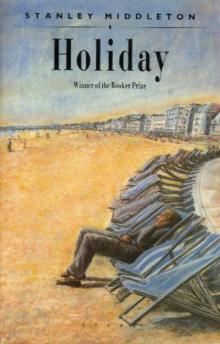

Valley of Decision Holiday

Holiday