- Home

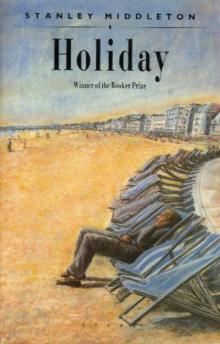

- Stanley Middleton

Holiday

Holiday Read online

Contents

About the Author

Also by Stanley Middleton

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Copyright

About the Author

Stanley Middleton was joint winner of the Booker Prize with Holiday. He lives in Nottingham, where most of his novels are set. Her Three Wise Men, his forty-fourth book, is available in Hutchinson hardback.

Also by Stanley Middleton

A Short Answer

Harris’s Requiem

A Serious Woman

The Just Exchange

Two’s Company

Him They Compelled

Terms of Reference

The Golden Evening

Wages of Virtue

Apple of the Eye

Brazen Prison

Cold Gradations

A Man Made of Smoke

Distractions

Still Waters

Ends and Means

Two Brothers

In a Strange Land

The Other Side

Blind Understanding

Entry in Jerusalem

The Daysman

Valley of Decision

An After-Dinner’s Sleep

After a Fashion

Recovery

Vacant Places

Changes and Chances

Beginning to End

A Place to Stand

Married Past Redemption

Catalysts

Toward the Sea

Live and Learn

Brief Hours

Against the Dark

Necessary Ends

Small Change

Love in the Provinces

Brief Garlands

Sterner Stuff

Mother’s Boy

Her Three Wise Men

Holiday

Stanley Middleton

To Selwyn and Mim Hughes

1

Light shimmered along the polished pews as the congregation heaved itself to its feet, hailing the Lord’s Anointed. Grain arrows waved darkly in the wood under the coating of shellac, the brightness of elbow-grease. Brass umbrella-holders gleamed, but the metal rectangle to house the name of the pew’s occupier had been allowed to blacken in disuse.

Edwin Fisher glanced at his hymn book as he listened to the voice of the woman next to him. ‘He comes,’ she sang, ‘with succour speedy, And bid the weak be strong.’ Her voice pierced, and she enunciated without inhibition so that a boy and a girl two rows forward turned round to stare at her. Their mother gently handled them back to propriety.

Fisher hummed, not opening his mouth. The walls of the church stood white, thick, while the narrow, pointed windows were leaded into small diamonds of cleanish glass. Above his head the gallery stretched, supported on metal pillars in regency blue. Typically, he smiled to himself, the chaste colours of the late eighteenth, early nineteenth centuries applied, not without success, in this Victorian building intended for dark browns and country cream. The woman next door lifted her head as sunshine caught the hair of the small boy who, now climbing on to his seat, leaned against his mother, tried to finger her hymn-book. ‘Love, joy, hope, like flowers, Spring in His path to birth.’

The congregation, Fisher guessed from the rear, were almost all middle-aged or elderly, and the majority women, in flowered hats, bonnets of convoluted ribbon and pale summer coats. Holiday-makers enjoying a full church, hearty singing, a popular preacher. There was, he noticed, no choir to speak of; two girls, an old lady and a grey-haired man occupied the stalls in front of the organ. Fisher did not like this: nonconformity as he recalled it demanded a large, fractious choir, bossy with prima donnas’ whispers, to drill the congregation’s singing into disciplined enthusiasm. The members here must be themselves on holiday or at home in the boarding houses laying the tables, basting joints.

The sun-bars angled down packed wild with dust-specks so that the air danced alive with energy between the areas of dim cleanliness. The congregation voiced the last verse with vigour, lashing the organ on, praising God in his tabernacle. ‘The tide of time shall never His covenant remove; His name shall stand for ever, His changeless name of Love.’ Silence settled heavily; the minister adjusted his hair, his preaching bands and the sleeves of his gown. Thus prepared, he pronounced the benediction and as the organist had gulped a final amen people flopped into their seats covering eyes with their right palms.

Edwin Fisher looked about.

Sunlight now dazzled as if it were reflected from the sea outside. The congregation was moving sluggishly, fingering silk scarves, exchanging bright words to the accompaniment of the B flat prelude from Bach’s Short Eight. Fisher was first from his back seat to the door where the preacher, shorter, less impressive than from the eminence of his pulpit, smiled and shook his hand. Outside light whirled as if the whole morning were one huge glassy fire fanned by the scuffle of wind into incandescent brilliance. Bankside Methodist Church. Dull gold letters. Morning and Evening, preacher, Rev. J. Parkinson Dewes, M.A., B.D.

The streets were quiet.

Presumably those for the beach had made their way there two hours back and were not returning for lunch. The contemporary pattern. Breakfast, into the car or down to the seaside, and not back before six for evening meal and television. So his fantasies about choir-singers bent over gas-stoves meant little; perhaps such dusted then, scraped mountains of spuds, weeded garden-paths or rested their bones with Sunday newspapers.

In spite of the sun the wind nipped at street corners in this east-coast town. On a main road now Fisher eyed an open stationer’s shop with its racks of cards, gaudy paperbacks, union-jack carrier-bags, buckets and spades. He loved this place with its covered arcades of metal, as if the industrial revolution had turned itself soft, displaying milder arts. He’d pushed here as a boy, wide-eyed, escaped from his boring parents amongst the panama hats and whitened plimsolls, listening to expansive talk, envying the means of generosity, delighted with girls, above himself.

Whistling, he decided against the beach, made for a pub.

The lounge, at three minutes past twelve, was empty, momentarily dark, and warm. Backed by shelves of bottles, each reflected in the mirror behind, the barman pulled a white coat over his shirtsleeves. He served Fisher without hurry, remarked on the sunshine and temperature before moving across to the other counter. Here it was as quiet as the chapel, but gayer, bittier; no place of worship boasted a plush carpet. Sipping his ale, Edwin Fisher considered the afternoon.

First, he must eat, but where? A sausage roll with his beer, or out to starched tablecloths and tips? When he’d visited this place as a boy, they’d called at the swing-chair weighing machine on the prom as they’d made their first trip to the sands. Vaguely he recalled his childish annoyance at the ceremony: mother first, then himself and his sister, finally father, and the weights inscribed on small cards while the old man chaffed the attendant who was all affability for six-pence. Fisher remembered the brown monkey’s face with its white streaks of eye-creases. And on Saturday morning, that day of sad exodus, they’d line up again, have the new weight recorded and subtract, they hoped, first from second.

These days everybody slimmed, sucked fruit, ate steak, eschewed ice-cream and beer. In those years of rationing, one did well to gain; to be fat was to be healthy. Fisher thought of his father, thin as a rake, swinging his tennis-shod feet from the chair of the weighing-machine as he groane

d, ‘Put another pound on, for heaven’s sake. They’ll think I’m pining away.’ And his wife would reply slyly, behind her hand, ‘Not with all that noise, they won’t, Arthur.’

Edwin had hated his parents then, for the shopkeepers they were. Obsequious, joking, uneducated, the finger-ends greasy from copper in the till, they drew attention to themselves. When the retainer ushered his rabble round the stately home, Father Fisher asked the first fool question, chirped the witless crack, was rebuffed in all eyes but his own with the guide’s calm, ‘No, sir. With respect, I don’t think that could be so ’ere, sir.’ Yet the old idiot had brains; he made his shops pay; he’d left his children tidy sums. And he’d read, though with a mind bent, young Edwin had decided, on trivialising.

‘Did you know, our Edwin, that Beethoven did multiplication tables on his death-bed?’

‘No.’

‘Well, he did. It says so here.’

‘What does it mean by “did” them?’ The boy was pushed into disguised objection.

‘Did?’ His father peered at the magazine or library book. ‘Don’t say. Learnt ’em. Or used ’em, I sh’d think.’

Back to his browsing. Not a thought of the music. The only Beethoven he could recognise was the Minuet in G that Tina plinked on the piano. If Edwin listened to the radio concerts, his old man complained.

‘Can’t you turn that thing down? It goes through you. Anybody can see you haven’t done a day’s work, or you wouldn’t want that racket.’

‘It’s Beethoven.’

‘No wonder he went deaf.’

Fisher never sorted out his father’s views on education, and could make little sense of them now. Both children went to university, and though Arthur grumbled about expense he paid up. Nor did he seem to envy their expertise. His magpie mind stored snippets of information with which he gleefully caught his offspring out, but he never attempted to organise or coordinate his knowledge into a system. His favourite reading, his son told him in moments of exasperation, was a set of children’s encyclopaedias.

‘Why not?’ Arthur would say. ‘Interest’s interest.’

His mother successfully taught herself what they were about, and could talk easily of ‘O’ and ‘A’ Level, university entrance, moderations, class of degree. When he thought about the matter now, Edwin wondered what sort of picture lay behind Elsie Fisher’s correctly chosen phraseology. But he’d never fathomed her, even when she was alive. Comfortable, cheerful, one would have guessed, not ambitious either socially or intellectually, she’d driven her husband on to pile away money and her children to become well qualified. A regular attender with her family at the Methodist Church, Vane Street, she’d never mentioned God or displayed herself to her family on her knees praying for guidance. Secretive, she’d lived openly; a plain woman who’d serve in the main shop, who would hold no office however undemanding in the church, she’d slave-driven her children and her husband so that they dared report only success to her. Even that she never praised fulsomely, but they learnt to look for a narrowing of the eyes and a slow nod to denote approval. Sometimes she’d say as when Tina passed for the high school,

‘If I were you, Arthur, I’d give them half a crown.’

‘Both?’ Assumed grievance.

‘They’ll learn to appreciate each other.’

‘If Ted’s naughty’ Arthur’d say jovially, ‘I s’ll have to smack the pair on ’em on that reckoning.’

‘If what she’d done isn’t worth five shillings to you, then don’t give it. I’ll find it from the housekeeping.’

‘And cut my teas down.’ Smiling under toothbrush moustache.

He invariably shelled out.

At thirty-two Edwin Fisher admitted his emotional immaturity when he thought back to those days, in that he felt again the embarrassment, the shame, the yearning to be elsewhere or some other body, which had constantly nagged him miserable. In his mind now he admitted his parents’ virtues; they were both compulsive workers, both knew a deep love for their children which they had no means of expressing to the clever, class-jumping offspring. Now that both were dead, he saw this, wished it otherwise, but failed to nail himself down to reason. Perhaps it was some fault in him. When he met his sister, a doctor married to a doctor, he began to build his barricades again, as though they shared some secret, desperate hostility. Not that she admitted much; distant, tweedy, sensibly detached, she regarded his approaches with amusement, but let them spend more than thirty-six hours together they quarrelled, not out of principle, but from buried habit. They were, he decided, still fighting for their parents’ affection.

Through the open window at his back he heard the shouting of children, the sharply raised voice of an adult. Curious, he decided in the end not to stand to find out the cause. Make your mind up when it’s too late; that was his line. He sipped his beer, exchanged three more words with the barman who returned flourishing a torch, examined the polish on his shoes and made for the door. He’d do without lunch, buy a pound of apples, walk. On Sunday? Anything could be bought at the seaside in summer. He pushed towards the beach in the day’s brightness.

As soon as he’d left the pavements for the soft, paper-littered sand he knew he was where he did not want to be. Nothing for him here but this wide stretch of fine dust, this shallow sea ten minutes’ march away and people in deck chairs, on rugs, behind gaudy wind-breaks, lying stripped and red, oiled in the sunshine. He’d take his shoes off, roll his trousers and paddle ludicrously as his father had done twenty years ago. Even when the old man had dabbled in the edge he’d kept his trilby hat on, preserved his respectability by attracting ridicule. That wasn’t true. Arthur Fisher had noticed nothing untoward in his behaviour, because there was nothing except in the mind of his jumping-jack of a son.

Edwin sat, emptied his shoes, fingered them on again. Here sprawled a man who’d left his wife, if that was the word, who had thus entitled himself to histrionics, to an emotional extravaganza, but whose person had decided to perform it again through his father’s antics. He stood, pulled at his jacket, slapped the pockets, told himself he’d forgotten the apples and made for the promenade.

The sun struck warm through his jacket in spite of the wind. Suddenly he walked livelier, stretched taller, recognized optimism. He’d like to speak to somebody, exchange afternoon banalities. The road leading to the beach, sprinkled with blowing sand, had become crowded, bright with swirling frocks, puffed-out chests, families with objectives. Nobody had a word for Fisher. No dirty old man, chuntering into his moustache, dragged his raincoat about him to beg for a match, a fag, the price of a drink. The people exchanged no confidences amongst themselves; a woman screeching about her sunburn was the exception.

Catching sight of himself in a shop-window he paused to admire the upright carriage, the thatch of hair, the distinction of nose, delicate hands. He did not posture long, but the moment did him good. For a dozen steps along the road he felt himself somebody, a noteworthy, though the scores passing paid him no attention.

He’d walk along the promenade; he’d take a bus; he’d buy a paperback and read it in a shelter along the front. On holiday. A free man. Without burden of wife, without children, a child. Now he swore, angrily, sourly, out loud, he thought, but no-one heard, turned a head, registered disapproval as he moved on.

‘Piss off.’

The sentence stopped him. A red-faced man had spoken to another who’d shrugged. Both wore raincoats. Both seemed sober, with hands in pockets, middle-aged artisans without axes to grind. Ten seconds before Fisher six yards away had noticed neither, but now there seemed a stoppage in the movement of the crowd, because of the fierceness of the delivery.

‘You heard what I said.’

The expression on the face of the second man did not change. He might have been mildly interested, but unembarrassed, not cowed. He nodded, sucked his thumbnail briefly, replied,

‘Please yourself.’

‘I shall.’

Neither moved; the few ne

ar them stood frozen; beyond that the frocks and slacks flapped forward to the sea. The first man swung away in a clumsiness of anger so that he cannoned into Fisher, mumbled an imprecation or apology, pushed away muttering. The second took his hands from his pocket, turned townwards, but without hurry. Fisher followed him for want of occupation. A hundred yards on, the man posted a letter, stooping to read the time of collection. The humdrum action surprised Fisher, who expected nothing ordinary of somebody who’d drawn attention to himself in the open street. Had he made some obscene suggestion? Or begged humbly? Did the two men know each other so that their exchange stemmed from earlier quarrels?

Fisher drew alongside.

In this street, Carlin Avenue, hardly a soul moved. Curtains were drawn on one side against the sun; lime trees flourished. Silence with vigour.

‘Lovely day, now,’ Fisher said.

‘Uh.’ A not dissatisfied grunt.

‘Wind’s a bit on the cold side.’

‘Um.’

Both syllables sounded friendly enough, belied truculence. Fisher, past now, could only press on. When he next looked back the man was lighting a cigarette; a minute later he’d disappeared, into one of the houses. Face wry, kidding, codding himself Fisher found his way diagonally to the main shopping street and thence to the promenade. Here he walked more briskly and considered the morning’s visit to the chapel. He’d no religious belief, no nostalgia, he told himself. A monkey’s mischievous curiosity had pointed him there and disappointed him at his lack of response. What he’d expected, what anybody expected, was now beyond him. A verse demanded attention, annoyingly.

Whether I fly with angels, fall with dust,

Thy hands made both, and I am there.

Thy power and love, my love and trust

Make one place everywhere.

He repeated the lines aloud; called them out again, modifying his stride to their rhythm. People passed, brightly, whipped by the wind, eyeing him, ignoring. George Herbert, he thought, as he wished for equivalent faith. In the seventeenth century Edwin Fisher would have believed, but grudgingly, in tatters, a sullen assenter, up with no angels. So Herbert.

Valley of Decision

Valley of Decision Holiday

Holiday