- Home

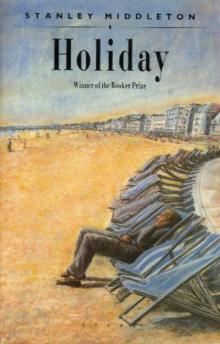

- Stanley Middleton

Holiday Page 2

Holiday Read online

Page 2

Suddenly, as a gust lashed, half pivoting him, and tippling the hat from the head of a paterfamilias, Fisher laughed, out loud, without reserve, as if the wind had thumped the sound from him. Then he ran, caught the spinning rim as it came up to him, and returning it, walked off cheered.

2

In his digs Fisher occupied Sunday evening at the bedroom window.

He’d half considered the furniture; polished veneer with curling scrolls at bed end and wardrobe door. The place was clean, and he’d plenty of room. Outside, he saw similar houses, red roofs with chimney-pots and disfiguring aerials, white windows where other visiters stood at washbasins, rubbed calomine lotion into their cheeks, slipped into finery. Dressing for dinner, one week of the year, they prepared for chips and chops, salmon salad, brown windsor, ice-cream.

He could hear footsteps, the occasional shout of reprimand that denoted children. Who came to these places, now that the package deals to Ibiza or Tangiers were so cheap? The conservative? The family man and dependants? The almost poor? He stopped the questions, began to lecture himself. He’d no right to this superiority. Let them crook fingers at coffee cups and boast of their cars, or be uncertain whether to laugh at or slap their boisterous kids they’d be better than he. Better? Humans? Even if they’d robbed the gas-meter to give themselves inclement indigestion at six-thirty in the evening.

He stood at the window, eyes above the lace curtain.

Outside it was bright still, and calmer. On the dressing table he’d put his writing case, which lay open. Perhaps, not this day, he’d write to his wife, a mild letter of description, with no mention of himself, no recriminating, merely a message so that she knew where he was, and in her anger at him could learn what this house, this street, this seaside was like. He’d not apologize or sulk or shout, but put down physical facts about rooms and holidays artisans and lilos until she screamed.

Downstairs a gong rumbled; footsteps drubbed the stairs.

He sat at a small table on his own, in the corner furthest from the window, under a tall hat-stand. His courses were brought by a smiling fourteen-year-old in a blue overall matching a headband. The meal was hot if tasteless, and undisturbed by the other guests who, brick red, seemed too tired for badinage. Even the children ate soberly, though one was whipped away to bed by a harassed mother before the main dish had been served.

One couple said ‘Good evening,’ but there conversation stopped. Over coffee two tablesful demonstrated that they came from the same town, the same street but as soon as they became hilarious Fisher drained his cup and went upstairs.

He cleaned his teeth and read for twenty-minutes E. T.’s memoir of D. H. Lawrence, sitting comfortably in a cane-chair, feet up on the end of the bed. Then he pulled his raincoat from the wardrobe, went down where in the small front garden the middle-aged couple from the next table stood hatless to inform him it was a fine evening, and to inquire if he was walking far. He did not commit himself, since he did not know, but the three sociably grouped themselves for a few minutes round a rose-bush, admiring the dark-red flowers, guessing, not hopefully, the name.

Not displeased with the encounter, Fisher spent the length of the street trying to place the man’s occupation. Then he made swiftly for the promenade, the beach, which, littered-thick, stretched deserted. He walked unsteadily in the sand because there was no purpose in this, nothing to see; already one or two men with pointed sticks speared crisp-bags and ice-cream cartons which they crammed into sacks.

The sun behind the promenade hotels threw long shadows, as an evening wind smartened the cheeks. Down by the sea’s edge, which he shared with a dog and a courting-couple, Fisher pampered himself, enjoying his hesitancy, unsure of what he wanted. He set off to walk northernwards along the coast, but half an hour of this convinced him he wished to do something else, so that he turned inland, past a caravan park and on to a flat road between bungalows and shacks. As soon as he found himself near the town’s centre, he turned into a back street pub, and ordered beer.

Here the walls were hung with bedroom mirrors and strings of fairy-lights; each table was glass-topped in green. With displeasure he realised from behind his jar that he recognised the man entering opposite, parking himself with back to the cushioned settle. David Vernon, his father-in-law.

Preparing to speak, Fisher eyed the other, who stared back without interest, as if he’d no idea whom he watched. Round marble-green eyes in a red face, Vernon looked like a cornet player at rest after an athletic solo, excited still, but recovering. Nothing in that, Fisher knew; Vernon played the violin with style, and his bucolic expression denoted no yokel’s simplicity. In the end, the older man nodded, but briefly, suggesting nothing, giving nothing away.

Fisher felt he should move; the place was not yet crowded, but in the end it was his father-in-law who stood, shuffled across. Smart golf-cap, white military-style mackintosh, checked tweeds, polished brogues, but no walking stick. The man made a performance of sitting down, pushing his stool, puffing and blowing, raising the tails of his coat.

‘You’re the last man I expected to see,’ Vernon said. Fisher returned no answer to that. ‘Not a bad little pub this. The landlord knows how to look after his beer.’

‘This is quite good.’

Both lifted, and sampled. Both replaced glasses on mats together. Vernon jerked on his belt, dug chin into collar, said,

‘I was sorry to hear about your business.’

‘Yes.’

‘Not my affair, mind you.’ The slight Welshness of his accent clashed with the bucolic English face. ‘If you and Meg can’t get on . . .’ He shrugged, pouted, saddened his expression. ‘Is it final?’

‘I should think so.’

‘Pity. I’m not claiming it’s your fault. She’s got something to answer for. One thing puzzled me, though.’ Did it, Taff?

‘Uh?’

‘Why didn’t you come to see me?’ Now Vernon sat upright, shoulders back, officer on parade. ‘I’m not saying I could have sorted this out for you, but I’ve a wide experience of matrimonial cases. As you know.’

‘Seemed no point.’

‘What does that mean?’

‘I’ve heard you say that once you became involved, yourself, with your client, you were lost, couldn’t stand it, couldn’t live with it.’

‘I see.’ Vernon bit his lip so that for a moment Fisher saw the young, thinly handsome solicitor of thirty years ago, the smartly intelligent scowl, the impression of undivided alertness.

‘It’s your own daughter.’

‘So I’m emotionally in . . .’ he changed the word, ‘entangled,’ liked it, repeated it vibrato ‘entangled.’ Jaggers’ bite at thumb now. ‘Yes. Yes.’ He picked up his pot, but did not drink. ‘Where’s Meg?’ he asked.

‘At home, for all I know,’ Fisher answered.

‘And you?’

‘I’ve gone to live with a colleague, share a flat.’

‘Does he know why? I take it the colleague is a man.’

‘Yes. A man. He knows I’ve left my wife. I told him.’

‘You sit and talk about it?’ Vernon insisted.

‘No.’

‘People do, you know. Intelligent people. University teachers.’ Jibing now. Uncertain, getting his own back.

‘They do.’

‘Just as some well-to-do solicitors spend their Sunday evenings in back-street pubs in sea-side towns.’

Vernon, not nettled, tapped his paunch.

‘I was tired. So we decided on a fortnight here. In the Frankland Towers.’ Most expensive. ‘Irene went to church, but I didn’t feel like turning out. I didn’t fancy swigging with the plutocracy. So I settle on the first little workmen’s pub I see. And whom do I meet there? My lapsed son-in-law, Edwin Arthur Fisher, Master of Arts, Master of Education.’

He drank, apparently pleased with himself for levelling the game. Fisher looked on him with something like affection, knowing this chitter-chatter was typical of the man and a camo

uflage for his intelligence. When he’d courted Meg, the father had invited him to play chess, and then, welcoming had fought hard, hating setbacks. That a grown man, stolid as a farmer, could so drive himself to win an unimportant contest, had amused and then frightened Fisher. Vernon had to establish superiority over his new rival, if only at chess. He could have squashed his opponent at bank-balances but that would have been nothing; intellectual victory, with best ivory men, alone had validity with this young academic dumped on him by his daughter.

‘Haven’t you been round to see Meg then?’ Fisher asked.

‘What do you think?’

‘You have.’ Fisher took spectacles from his pocket. ‘Did she say anything?’

‘Ah, that’s a question, now, isn’t it?’

‘Look,’ Fisher said. ‘I don’t want to make a meal of it. I’ve left her for good, and I think she knows that, and wants it. But I was married to her for six years, and that means something. If I could do anything for her, without going back or saying anything in person, I’d do it.’

‘How’s she managing financially?’

‘I’m continuing the mortgage and my solicitor’s arranging monthly payments.’

‘I’m not acting for her.’

‘I wondered.’

‘She’s an odd kid.’

They drank in silence now the pub seemed fuller of noise. Fisher set up fresh pints, and sitting said,

‘D’you know, I’d considered what I’d say to you if we met.’

‘Well, boy,’ Vernon answered, ‘we’re rational human beings, aren’t we? But Irene’s furious. She saw your marriage as perfect.’ He grinned, with mischief. ‘Perhaps she thinks Meg’ll be back, inflicting herself on us.’

‘Not much fear of that.’

‘You think not. Well, now. They didn’t get on; that is for certain. She’s a selfish bitch.’

‘Who?’

‘Naughty, naughty. You pays your money. Still, I was a bit surprised that it was you who went. If she’d have flipped off . . .’

‘She knows which side her bread’s buttered.’ Fisher.

‘Will she get a job, then?’

‘I imagine so.’

Again, they listened to the clatter of the pub. In the far room a piano clinked into hits from the musical comedies. Vernon, not without malice, hummed a snatch of ‘Love will find a way.’ In spite of his military appearance, his intelligence, Vernon’s tastes were simple; a drink, a television serial, Messiah at Christmas, hymn-singing half-hours on radio, watching some clever sod’s struggles in difficulty. On some good-badness scale how would one mark him? Though he was selfish, the trait wasn’t apparent. He did not scatter money about, but he was not obviously mean. He cared nothing for his wife and daughter; he never acted cruelly. He was an atheist who attended the parish church twice a month.

Now he sat, rubicund, bucolic, in a backstreet pub enjoying his evening drink and his son-in-law’s discomfiture. Fisher had no proof of this; he suspected that if he’d announced a reconciliation with Meg, Vernon would smile because he’d torment his wife with the news and guess, rightly, the date of their next major rumpus.

‘Penny for ’em,’ Vernon said.

‘Eh?’ Hard to hear in this din.

‘What are you thinking about?’

Fisher looked at the group of middle-aged patrons pulling up to their table, shedding caps, headscarves, coughing, ready to snatch shining drinks from the tray to toast each other.

‘You,’ he replied.

Vernon shook his head. The meat-faced leader of the new arrivals raised his glass, having handed out the gin-and-variables to his ladies, and said,

‘Here’s to all of you.’

Cheek dimpled, Vernon raised his glass to them, bowing with ceremony. This courtesy was well-received. In half-an-hour’s time he’d be explaining some point of law to them, with half the room agog, silent at his words.

‘And yours, sir.’ Meat-face.

Fisher gulped his beer away, wished Vernon good-night and made for bed.

3

Early next morning Fisher was up for a walk.

He’d woken uncomfortably before six and having shaved to the seven o’clock news on his transistor set, had shined his shoes and set out. Again there was an appearance of ceremonial to be kept up. His father had always taken him out for a trot on the promenade, a newspaper and a few improving words to the swing of a walking stick. The old man had been energetic; one granted that. As the pair gathered speed, and Fisher seemed to recall running quite desperately to keep abreast, his father would draw his attention to the clean air, the ozone, the smell of bacon frying, the morning sun’s sheen on the great windows of the sea-front hotels. He’d gesture with his walking-stick at the sand and reach some conclusion about last evening’s weather; they’d consult the tide-clocks and try to make head or tail of them, or the two-day old graphs of sunshine. ‘Finest hour of the day,’ Arthur Fisher would intone, handing his Journal with its inch-high headlines to his son. Edwin had not liked that; he was no dog. Besides if the paper were creased or rucked by a small sweaty hand, there’d be trouble when father, brushing his moustache bushy, sat down to page one and a few comments before the breakfast-gong.

Now Fisher walked smartly, swinging The Times.

As he’d bought this, he’d suddenly surprised himself making conversation with the stall-keeper in his father’s manner, friendly, hectoring, patronising. He’d totted up the change aloud, inquired about the wind’s direction, interpreted a sleepy reply and drawn the man’s attention to the photograph on the front page of a picture-daily. His dad had never worried himself about response; these dummies were scattered round his road to be harangued, or punned over. When Arthur Fisher holidayed, the whole world joined in, whether or not it noticed.

This morning the sea glittered in spoldges, ridges of shifting gold. The wind dipped from the east as the gulls spread wide wings and cawked. An artisan hurrying to work, leather snap-basket in hand, ignored Fisher’s cheerful greeting. Two girls on the far side of the road, skirt-ends lively, scurried prim-faced, one holding her hair in place with a spread right hand. The promenade was empty, and Fisher, tapping the metal railings with his newspaper had nothing to say or nobody to say it to. He lacked a son to race alongside him, to know the difference between a holiday father and a workaday, to admire, to be the recipient of convictions that would have evaporated with the day’s light.

His son had died.

Donald Everard Vernon Fisher was dead, had never visited this place, had not done much beyond crying for his mother and then, when she had needed him most to keep her sanity, and her husband, had failed to live.

A slap with The Times, a quick turn on the heel dismissed the dead.

At breakfast the young married woman on the next table made conversation. Her children had behaved well, but on leaving their stools had moved toward’s Fisher’s chair where they stood staring.

‘Hello, you young fellows,’ he said, deliberately sudden.

The deep voice startled them so that they gasped out loud and ran to their mother, clutching her slacks.

‘They aren’t being a nuisance, are they?’ He guessed she had assumed her most elegant accent, from the expression on her husband’s face.

‘Not at all.’

‘This is the first time they’ve been away. It’s strange for them.’

Fisher examined her fair shortish hair, gay jumper, straight back. She’d beautiful nails, but dyed to resemble black grapes. The husband, high-necked shirt, bushy long sideboards, collected the boys and ushered them upstairs.

‘Well trained,’ the girl said to Fisher.

‘So I see.’ She was determined to talk.

‘It’s nice to see the father taking a hand,’ the middle-aged man said, from nowhere.

‘He’s as good with them as I am.’

‘Why’s that?’ Fisher asked.

‘Well, he’s always done his share, and he can mend things. They’ve always

got a job for him when he comes home.’

This was smilingly approved round the room, so that it seemed that even the children there applauded this paragon of a father. The middle-aged man monopolised conversation, while his wife smirked modestly into her cup of pale tea. Fisher, buttering his last triangle of toast, thought the young woman appeared disappointed at his silence and the other man’s loquacity. He, not a bad practice, put the notion into plain words, altered the first verb to ‘hoped’, the second to ‘was’ and found himself not displeased. She’d be twenty-five, perhaps. A shop-girl.

She stood, pulled her jersey down, little breasts out-thrust; her eyes were bright blue, large.

‘I’ll go and see what they’re up to,’ she announced.

When she’d gone, the middle-aged man’s wife commented favourably on the children’s behaviour, told Fisher it wasn’t often you saw fathers giving a hand like that, and then mischievously, added that her husband hadn’t.

‘There was a reason,’ he muttered.

‘Oh, yes. I’m not denying it.’

Home counties. Minor civil-servant. Teacher. Shopkeeper. Foreman.

Upstairs Fisher deplored the decoration of his bedroom, picking up, fiddling with a spray of false roses he’d just noticed. This place was dustless, windows bright and curtains fresh from the cleaners, but without taste, a collection of polished, veneered plywood, and cheap pastel plastics. On the way up he’d seen the young father leading the smaller boy into the lavatory, and through the open door next to his own, the mother brushing the elder’s bright hair. All the time she was talking: ‘And you can make a castle if you like, or a motor-car, or a horse for Tony to sit on . . .’ Both the monologue and the moving hand pictured so youthful an energy that he envied her.

He’d nothing to do.

Looking down on the street he watched a family filling the boot of their car. They quarrelled and worked without direction, silently to the watcher, from time to time on the pavement in attitudes of contemptuous amazement. In the end they handed Grandma down, parked her in the back seat, wrapped her legs in a blanket, slammed the door and left her.

Valley of Decision

Valley of Decision Holiday

Holiday